I was born and brought up in the midst of war. My childhood and school life were all about war. Most of my childhood days were spent in active war, trying to dodge shelling, and hiding in bunkers to save our lives. These life experiences helped us save our lives during the final battle in May 2009. In the town where I was born and raised, there were frequent bomb attacks, and there were occasions when bombs fell on the schools we studied at. In those days, it was quite common in schools for students to be trained on how to protect ourselves from bomb attacks.

This conflict forced me to learn about the features of each bomb as a survival technique. Civilians and even children can guess which bomb is used by the sound it makes and the weapon that fired it. Most of us knew how a bullet would come from a particular weapon, how it would explode on the ground, what kind of impact it would have on the surroundings and humans, and how we should protect ourselves accordingly. During the final phase of the war, the Sri Lankan army bombed us from the air, from the sea and from all corners of the land in various new ways. Cluster bombs and 05G-type motor bomb attack weapons were used against us.

Thousands of people were killed during cluster bombings in the final stages of the war as cluster bombs can spread and detonate and kill large numbers of lives. While the Sri Lankan government was carrying out various bombardments from all sides, they carried out bombing from the sea and through Dora ships. At the same time, they also launched cannon balls from the sea. These are small ball-like shells harder to see with bare eyes. They explode the moment they make contact with anything solid, and when launched during the day, the bomb does not emit any sound or light. As a result, many people died in these bomb attacks during the daytime when they were taking a bath or defecating.

Bomb attacks are only capable of causing serious injuries to the human bodies, and it usually does not burn the skin like the skin in caught on fire. It is also not a self-igniting bomb unless it lands on something flammable. But one of the bombs dropped on our areas during the final war, caused such a cloud of smoke when it came and hit the ground that we could not even see those who were close to us. Those who were in the area where these bombs went off, had severe burns, and many died due to inhaling the fumes; I remember when we were displaced and hiding in bunkers, another civilian asked us to keep his infant child since his wife had been injured in a bomb attack where strong fumes and a chemical smell was emitted. The baby’s skin was scorched and ruddy due to the exposure. We believed it may have been some form of chemical or poison. We only know what we saw and experienced. To date, we don’t know what was used against us and what we were exposed to.

In February 2019, I stayed with my father when he was in the hospital, having been injured in a shell attack. A school in Puttumaththalan was converted into a hospital. It was there that I witnessed the full intensity of the war. Many civilians who were injured in the attacks were getting admitted to the hospital. With no adequate medicine or place, many injured were placed in the open and under the trees, suffering immensely. Many surgeries were also carried out under the trees in the open.

In November 2008 the Sri Lankan Government imposed a ban on the transportation of medicine required for aid to our areas. This caused an acute shortage of medicine, inflicting immense suffering to civilians. Only the ships of the ICRC that took passengers to hospitals in Trincomalee were in service. ICRC too given the injuries and deaths caused by the constant attacks of the Sri Lankan army near and around the ships, had to abandon its service around February 2009.

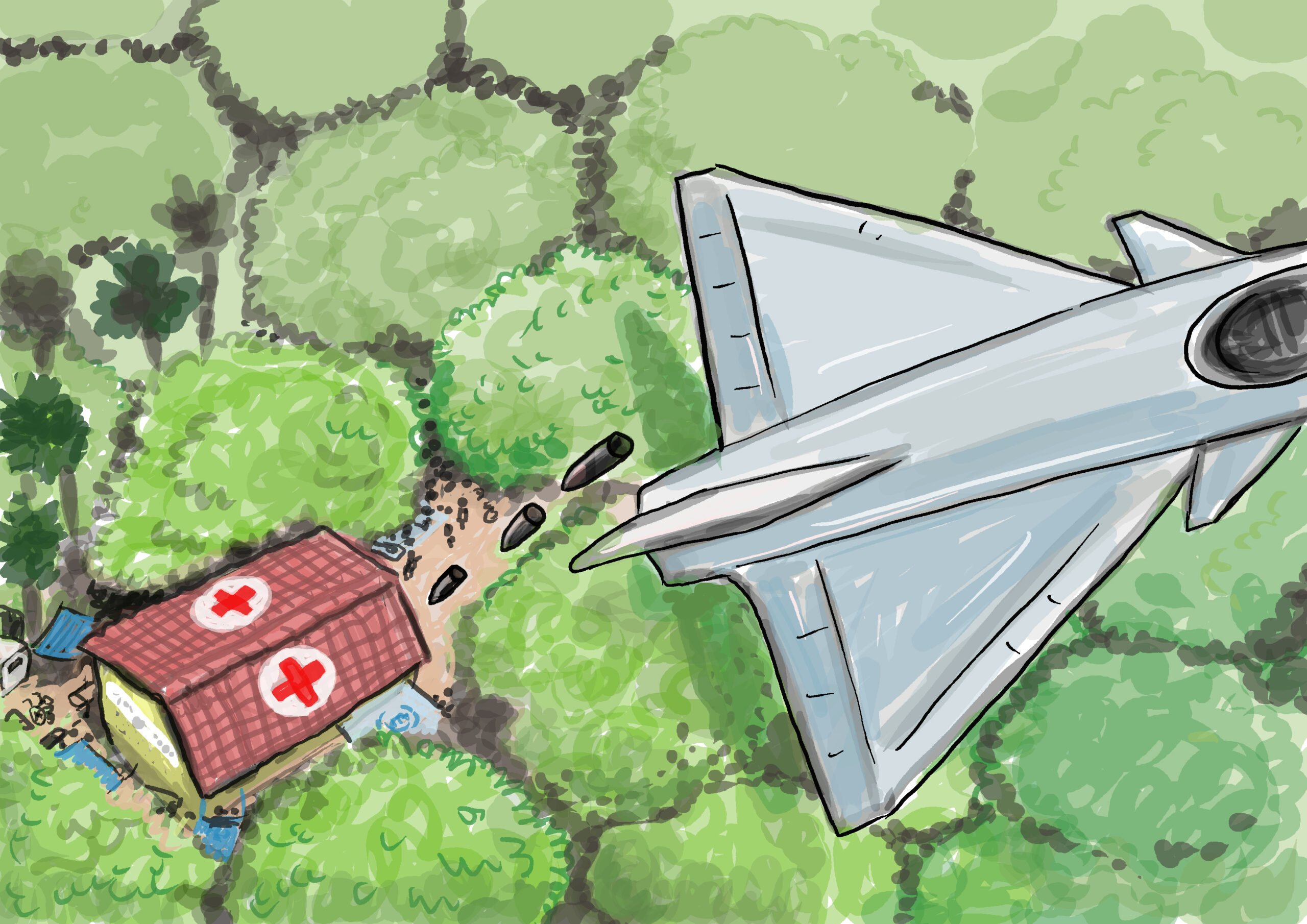

The army carried out attacks targeting places in which the civilians were staying. Even the hospitals where civilians were being treated were subjected to bombardments with the knowledge that they were hospitals. With the surveillance drones and the illumination provided by 10,000-20,000 W bulbs, they kept surveilling our areas, but notwithstanding this, they kept attacking the hospitals. Even though hospital symbols were drawn up on the rooftops of the hospital and school, it did not stop the attacks.

The army camp was situated within 600-800 meters from the hospitals in Puttumaththalan where my father and I were staying in. We could hear the announcements through loudspeakers demanding the surrender of civilians; we also saw them monitoring the hospital using telescopes. In spite of such close proximity, the army kept bombarding the hospital civilians were staying in, which led to civilian injuries and deaths.

Many civilians also died having been suffocated by the sandbags used for erecting makeshift bunkers falling on them. Since civilians were forced to move from place to place, they had to protect themselves by digging bunkers wherever they were staying in temporarily at the time. The areas closest to the sea, such as Mathalan, Mullivaikkal and Valaignarmadam, are not conducive to digging bunkers. Although women tried to sew their sarees into bags and fill them with sand so that they could be placed above the ground to protect themselves, the explosion caused by the penetration of the bags by shell pieces would dislodge all the sand. Many died of suffocation, having been caught up in such a collapse.

On the 16th and 17th of May streets full of civilians started moving from Mullivaikkal to Vattuvaakal with the intention of surrendering to the Sri Lankan army. I can still remember that the army personnel kept beating the civilians that came there to surrender with large batons and clubs and treated them like animals. We would be beaten up with large baton and clubs when we were passing by and would be ordered to sit in the middle of the roads. One minute we would be ordered to stand up, and the other minute we would be ordered to sit down so that the army would be protected from the counter-attacks.

When we were crossing Vattuvaakal to surrender, we saw stationed on the other side more than 250 – 300 army personnel. The uniform they were wearing and the way they conducted themselves signalled that they belonged to the higher-ups in the military hierarchy. When we reached Vattuvaakal after crossing the sea at around 4 p.m. in the evening, we saw five acres of open land enclosed with barbed wires. Between 16th and 18th May, we were herded inside this space like animals. The current Mullaithivu Court Complex stands in that place now.

We sat inside like slaves in that place for three days continuously with no arrangements for food, water or toilet facilities. When we, unable to bear the thirst, begged for water, the army dug up holes using a bulldozer and ordered us to drink the muddy water. The civilians were left with no alternative and drank the muddy water to quench their thirst.

During three days that we were caged inside – 17, 18, and 19 May – the army ordered LTTE members to come and surrender. At around 7.30 – 8 p.m. on 18 May, with the aid of informers, the army started dividing people into civilians and those that had connections to the LTTE. Around 50 members with their heads fully covered with black clothes assisted in this categorization.

We were, after that, ordered to stand in a long queue. Around 150 small checkpoints were erected, and the army started checking the civilians. It was only after we were stripped naked, and all our belongings were searched thoroughly that we were hauled up on the bus en route to civilian camps. In some checkpoints, male army personnel conducted the body check without giving due regard to the gender of the civilians. We heard civilians when they were waiting for the bus lament that some soldiers had stolen their money, jewelry and other valuables.

After such a heavy search, the buses took us at night and dropped us off in Omanthai at around 8 a.m. the following day. After ordering us to form a long queue another round of search and investigation started. Under the scorching sun, we were kept waiting in hunger and thirst. Anyone that tried to move away from the line was beaten up by the army with large batons and clubs. Women, elders and pregnant mothers were also made to suffer such ordeals. Then, at around 6 p.m., we were again ordered to board the buses, which dropped us off at Cheddikulam welfare camp at midnight. This so-called welfare camp where we had to stay was built in a forest situated in the middle of the hot zone between Vavuniya and Mannar; the forest had been cleared up, and several tents were erected; a single tent was allocated to two families.

For almost one and half months of our stay there, we did not have proper food, water, toilets, or access to medicines. It was through the grant of access to welfare organizations after one and half months, we managed to get some food, water, sanitary facilities and medicine, though the support available was far from adequate for the number of civilians in the camp. Since the army did not allow the civilians to leave the camp, the civilians who needed medical care had to wait for days before being taken to a hospital, as a result of which some of them died.

Many civilians who had escaped the ravages of war without water, food or medicines got afflicted with illness at the camp and died tragically without access to medicine. One of my friends too was among them. His family wept for the unfortunate fact that he survived all the ordeals of war only to succumb to illness while in camp.

We had to stay in the camp from May 2009 until we were finally allowed to resettle in April 2011. It was only when we returned to our land that we realized that the Sri Lankan government had not only destroyed our lives and our kin but had also ruined our livelihood to the extent that the recovery was almost impossible. Our houses, the vegetation and the fields that made us prosper along with the trees had been destroyed.

Although people lamented the loss of lives and their livelihood at the hands of the Sri Lankan State, they cried in grief when they witnessed that the Sri Lankan army had destroyed LTTE fallen heroes’ cemeteries. During the war, those that lost their relatives used to visit the cemeteries to commemorate their fallen relatives as if they were still alive and tried to find solace in such commemoration. On November 27 – the fallen heroes’ day – they would go to their relative’s tomb, clean it up, put flower garlands on it, light oil lamps and commemorate their memories freely.

The fact that people are still under heavy surveillance and suppression and are prevented from commemorating their fallen relatives clearly shows that the oppression of us at the hands of the Sri Lankan state still continues even after the end of the war. Our areas have not yet been demilitarized. The military is engaged in economic activities in our areas. Although they are trying to build confidence by establishing shops and maintaining good relations, people are not ready to trust them. To build confidence, the military goes to funeral houses, but people are not ready to accept them. The people are not willing to accept the myriads of actions the government is undertaking in the guise of reconciliation.

Having born and grown up during the war and having come through the devastation of the cruel final phase of the war, I have the courage and mental fortitude that I would manage any difficult situation. Although this courage gives me confidence, it also reminds me of the trauma that we went through. The solace I gain through raising my voice against the silent war that is being carried out against us by the Sri Lankan state in the form of land expropriation and colonization – which continues even after the end of the war – strengthens me to deal with and move forward from the trauma and loss that I have undergone during the war.