Having suffered many loss of lives, we are living with deep psychic wounds. The only reason why I still engage in social work with people is that there should be justice for all the people who were killed during the last phase of the conflict.

Last phase of the conflict! My god, I will never be able to forget it. How could we forget the persistent bombing of civilians using various kinds of bombs, shells, kifir bombing, cluster bombs, and phosphorus bombs and the countless deaths following the mutilations of the bodies that ensued as the result of bombings? Can we, forgetting all these, really engage in reconciliation talks?

In August 2008, my family and I started to move out of our village. Moving from Paranthan to Visuvamadu to Udayarkaddu, we faced constant bombardment at Udayarkaddu, and as a result of which, we moved to Irudumadu. Having stayed for a week in Irudumadu, we moved again to Thevipuram and then to Puthukuddiyiruppu, where we stayed for two months. One night around 9 p.m. during our stay in Puthukuddiyiruppu, cluster bombs rained down, causing the death of several who tried to find shelter inside the bunker. Only then did I learn for the first time about cluster bombs. Falling down from the plane, in the initial blast, they splinter into several pieces, each of which will then detonate, capable of causing devastating impact wherever they fall.

As the Sri Lankan army was closing in on Puthukuddiyiruppu, we moved to Valagnarmadam. Three families stayed in a tiny bunker for one night. The Sri Lankan army, as usual, continued to rain down bombs incessantly. As I was washing the appliances at the entrance of the bunker to make tea, a bomb went off near the bunker, splashing some water-like liquid over me. In fear, I jumped back into the bunker. But we heard loud cries from people nearby.

A few moments later, an older man entered the bunker carrying in his hands two babies drenched in blood. Taking the babies from him, we cleaned away the blood using the clothes we had. In that blast, all his family members, including his wife, son and daughter-in-law, perished. Around this time, my sister, seeing that my dress was starting to corrode and disintegrate into tiny grey-coloured pieces, asked me perplexed, ‘Child, your dress is also corroding and wearing away?’. When I touched my dress, I saw it withering away thread by thread. I felt a burning sensation in my body. When my brother-in-law tried to fetch me another dress to wear from the clothesline, they too, disintegrated into tiny grey-coloured pieces. It was only then I realised that the Sri Lankan army had used phosphorous bombs against us, and the liquid splashed over me was something that emanated from them.

To escape the relentless bombing, at midnight, around 12 a.m., we packed ourselves and started to move towards Mullivaikkaal. On our way, we witnessed around 15-20 families taking shelter in a house situated near a community centre. We decided to stay there because it had a well and a bunker. There, I witnessed the death of 15-20 people in a single attack. The scene of innocent women who had been washing the rice for cooking and those who had gone out to discharge the curry from the cooking pot, lying there dead, is still alive vividly in my mind’s eye. Since the army was advancing, we moved towards the coastal areas of Mullivaikkaal.

While staying there for a month and a half, I was requested to attend the childbirth at the Maancholai Hospital of the wife of someone whom I knew through my son. I went with them to the Maancholai Hospital. Upon the delivery of the baby at the hospital, they immediately handed me the baby without even wiping the blood away. As I was wrapping the baby in a cloth, a shell fell down and blasted near us, catapulting both me and the child away. While falling, I hugged the baby to my belly and swerved and landed on my back so as to protect the baby. As I was standing up, I witnessed an old man crying out for medical help, clutching in his hands his small intestine that popped out through the laceration in his belly. How do we provide medical aid for him? The constant bombardment, including against the hospital, had forced the hospital nurses to find shelter in the bunker. Thus, they could not help the old man. All the injured were placed under the makeshift in front of the hospital. I saw, on that day, more than 500 wounded there. Even the areas that the Sri Lankan state had designated as ‘Safe Zones’ were subjected to heavy bombardments. The TRO organisation, one day, was doling out porridge, to obtain a portion of which, hundreds of civilians stood in line. I cannot forget the carnage I saw following the shell attack on the civilians gathered there; women, children, and elderly lay dead with plates in their hands.

My husband had been working with a non-government organisation. Following its call, he went to its place to report to work. I could only contact him once a week. I had to trample on the dead and walk past the injured every time I went to meet my husband. Every day, there would be a torrent of phosphorus bombs, cluster bombs and kfir bombs falling down. On 15 May 2009, the Sri Lankan army had advanced really close. At around 11 p.m., the LTTE announced, “Amma! If the (Sri Lankan) army comes, please go; we are not going to fight but are going to withdraw; those that want to leave can leave”.

At around 3.30 a.m. the following day, the army encircled the area. From inside the bunker, we could hear them conversing in Sinhala nearby. They ordered us to get out of the bunker. To reach the place that the army directed us to go, we traversed through and tripped over thorns and pits along the way. We were finally brought in and clustered around a Palmyra grove near the Shiva temple. More than 2000 people were crammed into the area. Having been doled out biscuits and water bottles, we were ordered to board buses, which took us to Iraddaivaikkaal.

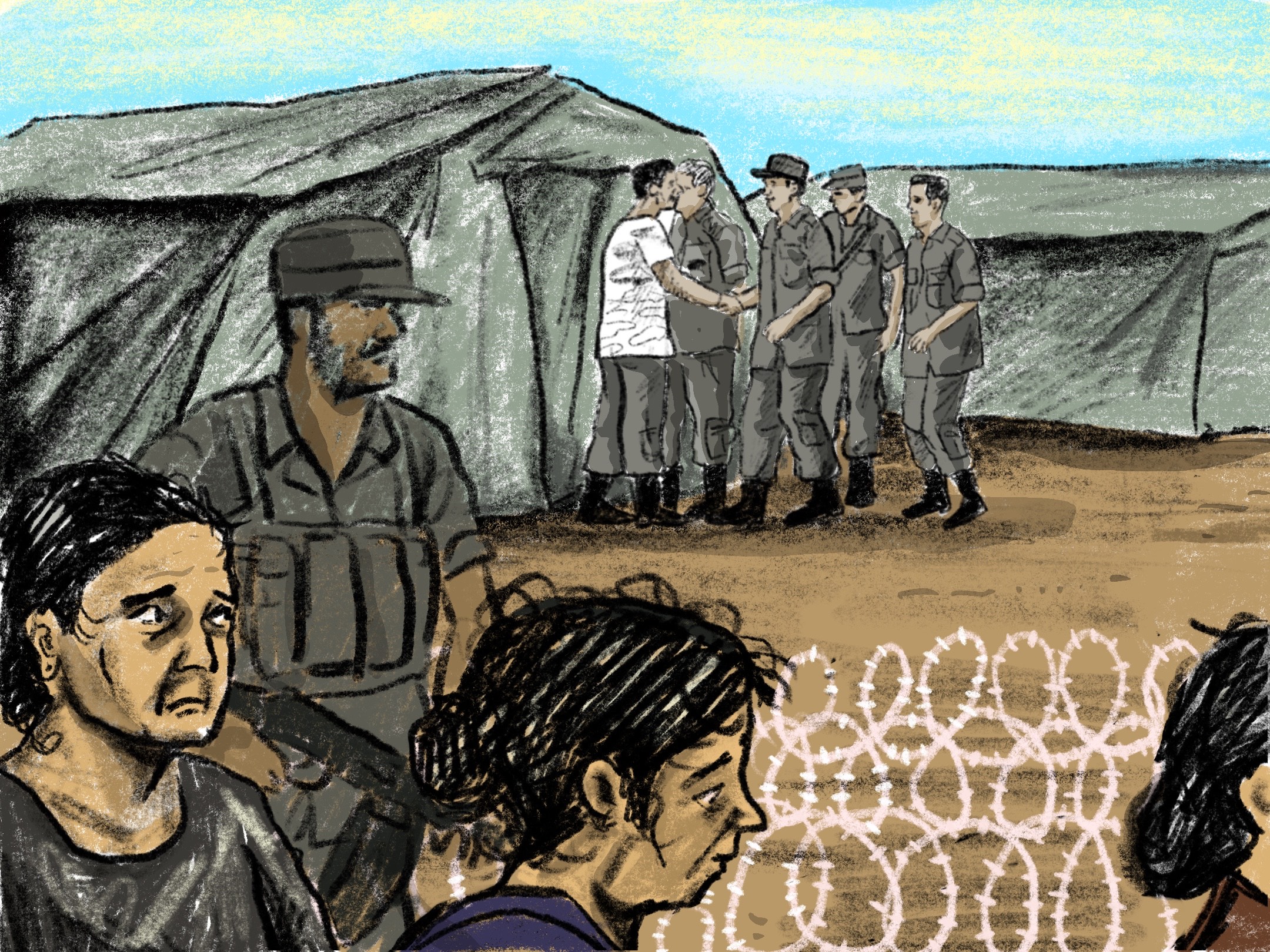

In Iraddaivaikkaal, we were clustered into different categories: LTTE members, those who worked with them and civilians. There were green tents. Screams of girls were coming out of the tents. The squalls, “Amma! Save us! Anna, save us! Don’t you realise what is going on here? Somebody save us, please?”, are still ringing in my ears. I, along with my children, my sister, her husband and their children, stood in line at that place till 6 p.m. We could hear the girls screaming the entire time. How can I forget the army personnel outside the tent laughing and congratulating the personnel upon their emergence out of the tent, shaking their hands and giving a tap on the shoulder? Witnessing the girls’ parents wailing outside the tents was unendurable.

In Iraddaivaikkaal, we were clustered into different categories: LTTE members, those who worked with them and civilians. There were green tents. Screams of girls were coming out of the tents. The squalls, “Amma! Save us! Anna, save us! Don’t you realise what is going on here? Somebody save us, please?”, are still ringing in my ears. I, along with my children, my sister, her husband and their children, stood in line at that place till 6 p.m. We could hear the girls screaming the entire time. How can I forget the army personnel outside the tent laughing and congratulating the personnel upon their emergence out of the tent, shaking their hands and giving a tap on the shoulder? Witnessing the girls’ parents wailing outside the tents was unendurable.

I only had a handbag while standing there. In it were 100,000Rs and a golden chain. When the army was scrutinising my bag, my attention was diverted to somewhere else. My nephew shouted, “Aunty! The army is taking the cash lump sum from your bag”. As I looked back, I saw the army personnel pushing the cash and a golden chain into his pocket. When my sister’s husband tried to ask the army personnel in what little Sinhala he knew, “Mathaiya (Sir)! Sally, Sally (cash, cash), the personnel raised the bottom of his gun to hit him. I opted not to push it any further out of fear. Many people have said that the army had appropriated their money and jewellery during such scrutiny.

I only had a handbag while standing there. In it were 100,000Rs and a golden chain. When the army was scrutinising my bag, my attention was diverted to somewhere else. My nephew shouted, “Aunty! The army is taking the cash lump sum from your bag”. As I looked back, I saw the army personnel pushing the cash and a golden chain into his pocket. When my sister’s husband tried to ask the army personnel in what little Sinhala he knew, “Mathaiya (Sir)! Sally, Sally (cash, cash), the personnel raised the bottom of his gun to hit him. I opted not to push it any further out of fear. Many people have said that the army had appropriated their money and jewellery during such scrutiny.

From there, we were sent on buses to Omanthai. There, near a school, we were interrogated again. Interrogations were being conducted, having divided the people up into different categories: LTTE members, those who helped them and those who worked with them. The LTTE former combatants were herded towards Thanddikkulam, claiming that they would need to be taken photos of. We, however, could not see them return during our stay there. From Omanthai, we were sent to Ramanathan camp by bus. We escaped from one hell only to end up in another. There was no sound of bombs going off. But we cannot really forget the effect of thousands of civilians being herded together in a constricted space: that we stumbled on human feces when we moved. Going through these sorts of pains and torments, we were finally allowed to resettle in our village in 2010.

Although 15 years have passed since we faced such horrors, they are, to this day, still deeply imprinted in our minds. In the name of reconciliations, we are asked in many workshops to forget and forgive these memories. How can we really forget the things we witnessed, the deaths, and the woes? These memories will haunt us to our graves. Be that as it may, there must be justice for all of them. It is the hope of finding a solution to them that drives me to engage in social work. It is only in the hope that, even if we do not see justice, our children will, that I am continuously toiling away.