It is the spirits of those pregnant women, children and elders that died in the Mullivaaikkal massacre that still impel me to continue the struggle to find those that have been forcibly disappeared.

Even when I am exhausted and try to abandon the struggle, the spirits of our relatives, who died in Mullivaaikkal, cry out to me as if they are in front of me: “Oh god! Are you leaving without us? Have you forgotten us? Has our blood dried out? Are you abandoning us even after seeing our blood spilt? Are you exhausted? You ought not to be tired. This injustice should not happen to our community. The Tamil community should not be destroyed.” It is these thoughts that propel me to engage in the struggle to find the forcibly disappeared.

How can I forget the memories of abandoning the injured that we encountered on our path, who, clutching our legs, begged us, “Please carry me with you”, as my husband and I, carrying our two-year-old child, tried to escape the conflict, because we were running for our lives and therefore could not carry them with us?

Even now, whenever I visit Mullivaaikkal, all I remember is how many have died there. Whenever I see and pass the places we had previously stayed at when we were displaced, I see in my mind’s eye those that had also stayed there waving their hands, blinking as their bodies lay stiff, running away, lying down and crying out loud. I, to this day, dream of bombs falling and people running for their lives and dying. I cannot forget the Mullivaaikkal memories, no matter how many years pass by.

We did not feel the heat when staying under the scorching sun in that open clearing with no buildings or trees in the final days of the conflict. We slept under this blistering sun; we walked when the day was burning; we, under this torrid sun, held on to our lives. It was this sweltering open clearing that gave ample space for the Sri Lankan Army to kill us off easily.

Cluster bombs, air bombs and shells rained down upon us as we, believing the Sri Lankan Army’s assurances that ‘all civilians will get protection if you plant and fly a white flag wherever you are located’, tried to surrender in Mullivaaikkal, carrying white flags.

Whenever I visit these places, I am bombarded with the memories of running for our lives when the bombs rained down on us, of the bodies of the dead that were trampled under our feet and of the injured who were on the cusp of dying and whom we ignored in our hurry to save ourselves.

If I take a handful of soil from Mullivaaikkal, it, to me, would still reek of the bloody corpses that laid there. How can I forget them?

My child was afflicted with diarrhea during the bloodiest days of 14th, 15th and 16th of May. When I was outside trying to boil water for my child in a broken pot, a shell fragment hit my belly and penetrated the flesh. My husband, believing that I would die without treatment, tried very hard to take me to the hospital. As we waited on the Mullivaaikkal coast for a boat or ship, none came. My wounds started to stink, and I could not breathe. Owing to this, on 16th May, my husband and I started to leave the Mullivaaikkal coast with our child.

When we reached the border between Vattuvaakal and Mullivaaikkal on the 17th of May, we had to cross the body of water bordering Vattuvaakal. There was no bridge back then, and the only way across was to get into the water and walk to the other side. As we crossed the water, we witnessed countless bodies of those shelled down and massacred by the Army while trying to cross this same water days before. Many of the dead were from Jaffna, murdered in the bombardment aimed to prevent them from crossing. Some of the bodies stood in various positions: some were bent over, hands clasped together as if making a plea, some were squatting, and some had their hands raised like they were surrendering. More than 300 civilians, including pregnant women, young children and the elderly, had been massacred there.

As we trotted on and waded through their bodies, we arrived at Vattuvaakal. Upon arrival, my son and I became thirsty. Unable to bear the thirst any longer, I drank from the water filled with bodies that we had just crossed and gave a few handfuls to my son. It was upon my arrival at the army camp in Vattuvaakal, precisely when looking at the pristine condition of the water they gave me to drink, that I realized that the water I had drank had been soaked in our people’s blood.

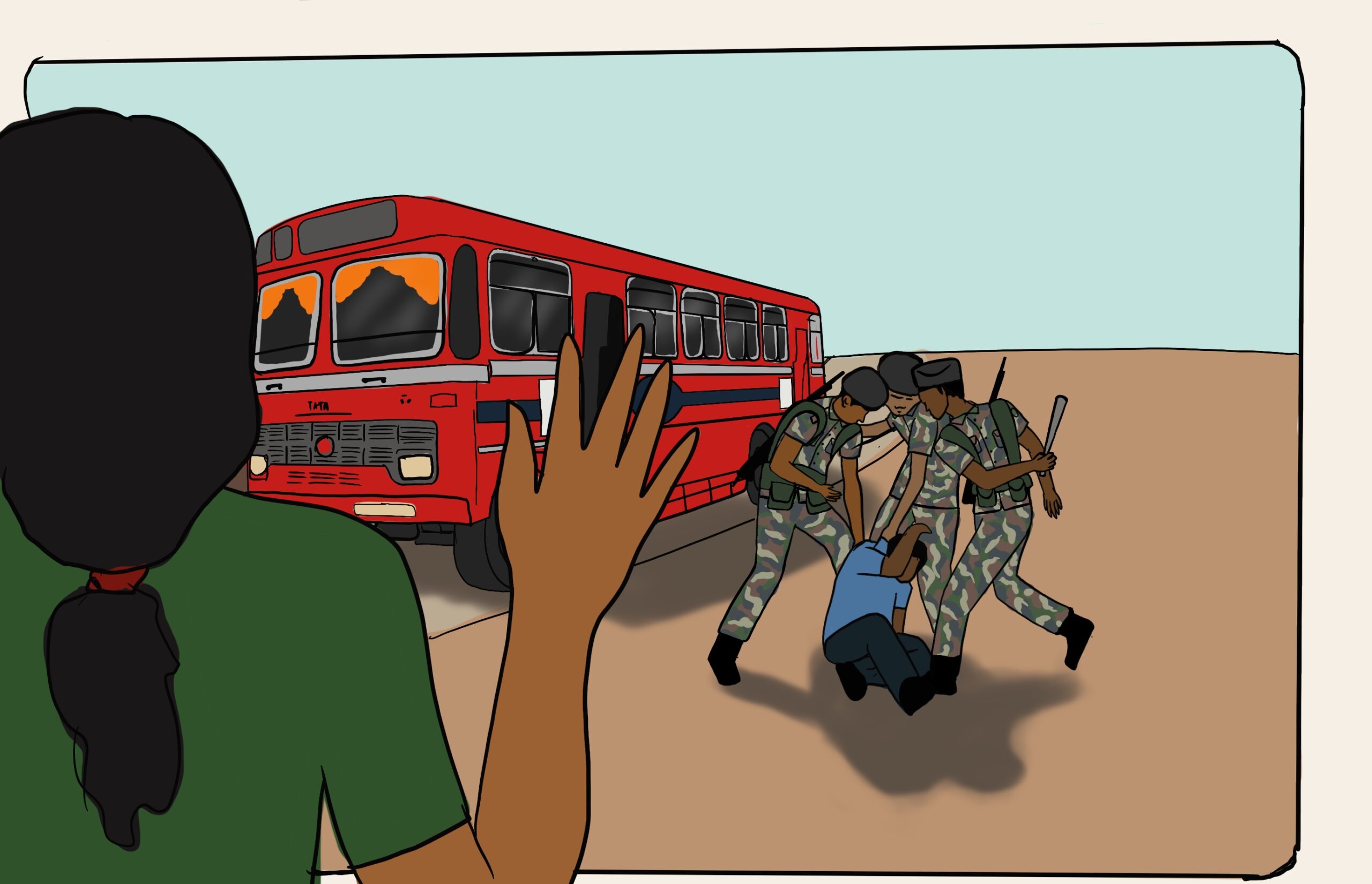

Upon our arrival in Vattuvaakal, the army called my husband’s name and demanded that he surrender himself. My husband tried to plead with the army, vowing that he would surrender after seeing me safely admitted to the hospital. As the army beat him, I begged him to leave, to which he replied, ‘No, you must live, and if I went to jail, who will look after our son?’. My husband kept pleading with the army, saying, ‘Sir, please! Sir, please, she is wounded, sir!’ in broken Sinhala, all the while being beaten by the army and pushing me onto the bus to Mannar hospital. I cannot forget any of this.

When I looked outside the window of the bus, I saw the army continuing to beat my husband. I cannot forget what he shouted out loud in reply when I timidly called out to him: ‘I do not know what you are going to do alone. Take care of our child. I will return even if it takes ten years. They are only asking me to surrender. The Sri Lankan government will release us.’

How can I forget the memory of my husband being taken away towards the direction of Omanthai, in a red-colored bus belonging to the Sri Lanka Transport Board, when he surrendered to the Sri Lankan Army on 17th May 2009 at 9 a.m.? It is these unforgettable memories of Mullivaaikkal that, in many ways, remain the driving force in my quest to find justice for my husband and other relatives that disappeared along with him.

I still doubt whether we will ever recover from the memories of the last days in Mullivaaikkal, even if our just and fair demands are fulfilled one day.

To see this story in Tamil please click here. To see this story in Sinhala please click here.