Born in Amparai, Deepa’s village was lush – surrounded by paddy fields, behind it a river and vast forest. One afternoon, when many were working in the fields, the army got news that there was LTTE presence in the area. The army started firing at civilians working in the paddy fields, injuring and killing many. “Our Appa was shot – they hit him while he was irrigating the paddy field. They hit him at the knees and with that he was unwell and stayed at the main hospital for 10-15 days and then when he came home he died,” says Deepa. This was the mid ‘80s, and the beginning of Deepa’s aspirations to fight in the armed struggle.

“At the age of 15 I had a picture of Thalaivar [‘leader’- referring to V. Prabhakaran] in my pocket,” she says. Deepa and other youth within the community would buy sarongs, towels and other goods and secretly transport it to those in the LTTE. “We would dress in a black skirt and shirt in the night so no one could see us,” she says. They would travel in the dark and store the items in homes of supportive Muslim families for safety.

Deepa recounts the journey from the East to the North when she first received training, the details crisp, even twenty years later. When a fellow cadre was injured during battle, Deepa tied up his wound using a piece of a sarong and carried him on her back. Recently she spotted her fellow comrade in Paranthan and he was happy to see her.

Years later, Deepa was injured in battle leading her to be paralyzed. She lived under the special care of cadres in an LTTE facility. “It was like I was dead,” she recalls. “Sometimes when sleeping my hand would go behind my back and I wouldn’t know where my hand was. I would scream loudly – I can’t find my arm! Come quick! They would come running and they would turn me around and show me my arm.” Deepa was determined to use her strength and will power to get herself walking again. “I had a room with a barred window and when I was alone I would struggle and get up using the bar. I could lift one leg and would drag the other and I would stand and start shaking. Once I started shaking, I would call for help and they would come yell at me saying – who told you to do this!” But her continued effort brought back sensation in her body.

“One day they sat me down to bathe me… I was sitting there and there were ants walking in a line and then someone said – why are there so many ants? I looked and the ants were surrounding my foot. All around my toes there were thousands of ants biting my skin and I didn’t know. I can’t forget that. Now even if there’s one small ant I can feel it… I get startled quick now if an ant bites me.”

It is with much love and sadness that Deepa speaks about the cadres that looked after her. “They cared for me as if I was a baby and they were my mother.” Today, in her home in the Vanni, she has fallen ill several times. “These 27 days I have been laying on this bed, everyday, everyday minute I think about my fellow cadres.” Her young daughter has been her support. “She will make plain tea and then go to school with an empty stomach. She’ll say –Amma don’t get up for anything, that’s how we live our lives. If Anna [elder brother, referring to the LTTE leader] was here he would know what to do for Maveerar families and for former fighter families… today we have become orphans.”

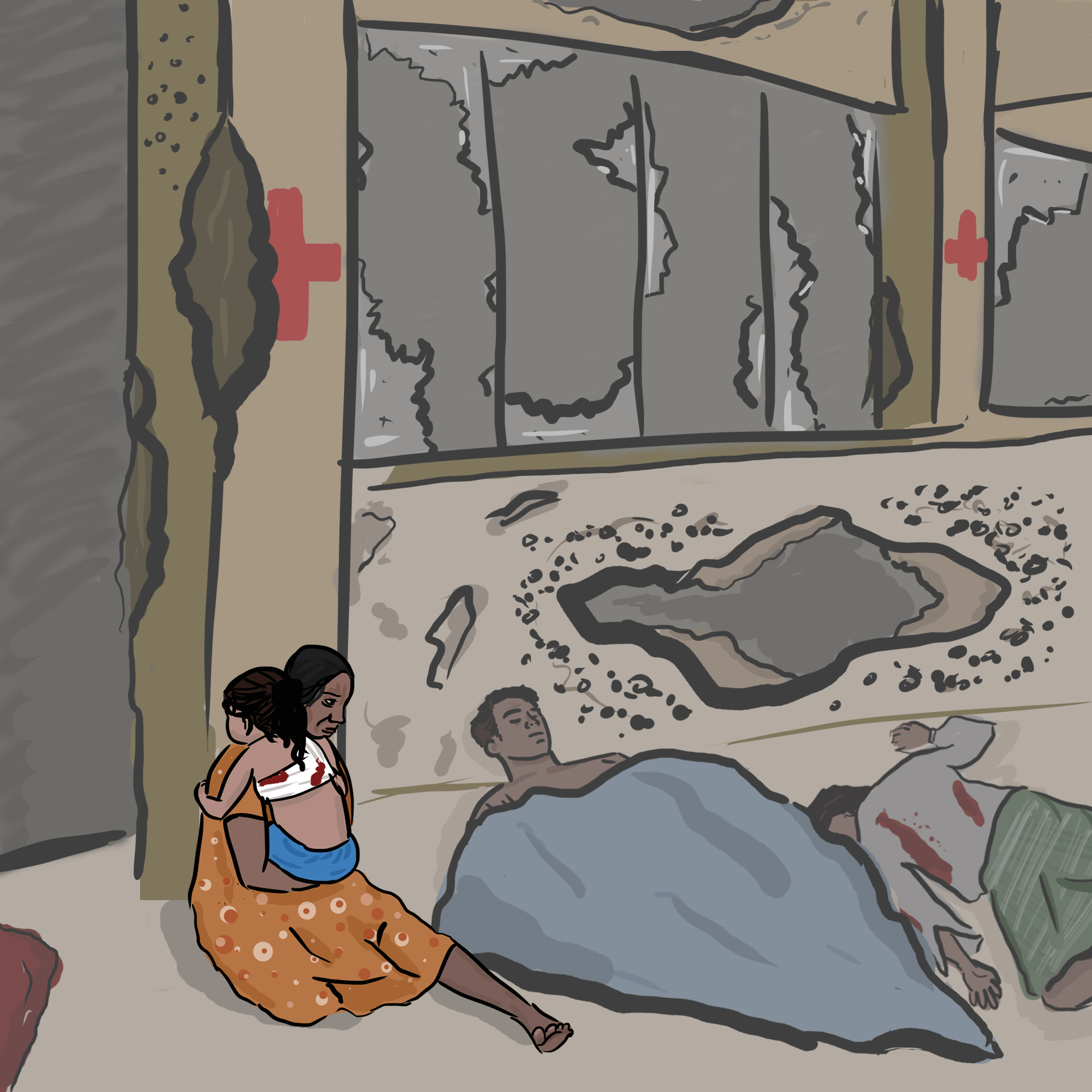

Upon the death of her husband, Mohan, Deepa felt abandoned. Mohan, a former cadre like Deepa, surrendered at the end of the armed conflict in 2009. During the final stages of the war Deepa, Mohan and their infant daughter were travelling together with the thousands of other displaced Tamils in Mullaitivu. They were at the Mathalan school that was being used as a makeshift hospital when it was attacked by government forces. “Everyone sat in a line under a hut, the roof made of steel sheets. When we were there, my daughter was sleeping in the middle between my husband and I. Then rounds started coming and we took cover by putting our faces into the floor but we never expected for a shell attack. We were taking cover from the rounds and a shell fell on our hut – an RPG shell. A pregnant woman who was sleeping beside me died right away.” The shells landed on the makeshift hospital, surrounding huts and ambulance vehicles. Although both Deepa and Mohan were badly injured, they managed to protect their daughter.

Upon the death of her husband, Mohan, Deepa felt abandoned. Mohan, a former cadre like Deepa, surrendered at the end of the armed conflict in 2009. During the final stages of the war Deepa, Mohan and their infant daughter were travelling together with the thousands of other displaced Tamils in Mullaitivu. They were at the Mathalan school that was being used as a makeshift hospital when it was attacked by government forces. “Everyone sat in a line under a hut, the roof made of steel sheets. When we were there, my daughter was sleeping in the middle between my husband and I. Then rounds started coming and we took cover by putting our faces into the floor but we never expected for a shell attack. We were taking cover from the rounds and a shell fell on our hut – an RPG shell. A pregnant woman who was sleeping beside me died right away.” The shells landed on the makeshift hospital, surrounding huts and ambulance vehicles. Although both Deepa and Mohan were badly injured, they managed to protect their daughter.

Eventually after fleeing into army territory, Mohan was taken by the army on a stretcher. Deepa and her daughter travelled to Omanthai where Deepa too was taken to the hospital. Searching all over the emergency ward for her husband, Deepa was assisted by a nurse who said that a man was admitted by the description she gave but he is unable to answer any questions – perhaps this was Mohan. “I went and stood in front of him and my husband didn’t know who I was he was that shocked. I showed him our child and he didn’t notice and was just looking around.”

After weeks of recovery they were all moved to a camp where they were then told that they must move again to undergo the rehabilitation process for former-cadres.

“They loaded us and said – we are taking you all to one place, one month of rehabilitation. Even if you were a part of the LTTE for one day we will give you one month of rehabilitation. For those with families we won’t separate your children, we will keep you together when giving you rehabilitation. But that was not maintained and once the bus reached the camp all the women and children were told to get off. We got off. But I couldn’t carry my child so I told my husband to get off the bus and give her to me. I managed to hold her on my shoulder as she was sleeping. ‘Come inside come inside’ the soldiers said, as if they were going to shoot us. I was standing and looking up at the bus thinking Mohan would look at me but he fell asleep on the bus and didn’t look at me. I kept turning around and looking till I lost sight of the bus. The bus left and I didn’t see him for three months, didn’t know where he was.”

Throughout the three months that they were separated, Mohan sent Deepa 21 letters – all of which were only given to her once Mohan died, a week after she was finally able to see him.

Before Mohan’s death he was brought to meet Deepa. “When they brought them there was barbed wire between us and they let us talk for 15 minutes,” she says explaining that Mohan was interrogated about his time in the LTTE. “He told me since you’re with a child they may leave you, if they leave you take good care of our child,” Deepa recounts adding he told her, “they may leave me or they may take me to another camp, you take good care of our child.” A few days later Deepa was given the devastating news of her husband’s death. “They took me to the mortuary and the army commander said – your husband had a heart attack last night,” she says clear that she is doubtful of the truth of this. “I wasn’t able to do any of the rituals that I was supposed to… I died that day,” Deepa says.

Weeks later Deepa was released from rehabilitation, but like many former cadres, state surveillance continued and the CID really bothered her. “I wouldn’t go anywhere because if I go out they ask around everywhere,” Deepa explains. There have been times where Deepa has been asked to give information in exchange for livelihood support – information such as which former cadres have not gone to rehabilitation. “I don’t want that. Our children, our dreams can’t just die with us. We aren’t ready to sell out for them,” she says.

Today Deepa is persistent in trying to find a sustainable livelihood. She has been let down by many including those in the Tamil diaspora. “I don’t want to beg anyone and I want to stand on my own two feet. I want to start my own business, that’s what I yearn to do.”

“I raise my child telling her every single experience that we’ve gone through…this is what happened, this is how your mother was orphaned,” Deepa tells her daughter about the struggle she fought in and what they fought for.

“This is how I make my father and her father’s history known to her.”