I am 30 years old. I have lived in Puthukudiyiruppu since I was born. I have two sisters and a brother, all of whom are married and live on their own. I live with my father and mother. I had heard stories of fighting in places such as Jaffna, but had never seen it firsthand. It was only in 2006 that I witnessed the war personally, which turned our lives upside down. I was only 14 years old in 2007 when I understood the full extent of the war and its devastation.

In 2009, I should have finished 10th grade and started G.C.E. Ordinary Levels. In January of that year however, the war came to us. We went to our grandmothers’s house in Ananthapuram, while our neighbors started moving towards Thevipuram. In March 2009, numerous tents were constructed within a constricted space in Ananthapuram and started to overflow with displaced people. It was then that the cluster bomb attacks began. Situated opposite our land was an LTTE camp, where there were some LTTE cadres that we knew on duty. We would hide inside the bunker upon hearing the sound of bombs, though back then, we did not know the bombs we faced were cluster bombs. We did, nevertheless, witness those bombs explode into smaller bombs upon hitting the ground, with each bomb then detonating. When I looked out of the bunker at one point, I saw a person running around in agony, engulfed by the fire from the bomb that had exploded. Since I had never seen anyone die in front of my eyes before, watching him die was really painful. When we came out of the bunker the next day, we found out that the houses and the surrounding trees had been burned down due to the cluster bomb attacks.

In our house, we had an idol of Jesus Christ. The day prior to these attacks, the idol had fallen down, and its head had broken apart; my mother, upon seeing this, decided that it was a sign that it was no longer safe for us to stay there. Moreover, adjacent to our house was an LTTE juvenile rehabilitation camp,, and the probability of it being subjected to an attack was high. Therefore, clutching in our hands whatever belongings we could get from our house, we moved out and traveled to Valaignarmadam with others. Deciding that Valaignarmadam was also not safe for my elder sister and her one-year-old baby, we decided to leave for a place called Mathalan.

The pre-school in front of the place where we stayed in Mathalan had been converted into a hospital, where the wounded were being treated. My parents tore the sarees that we had brought with us to pieces and used them to assist in bandaging the wounded. At this point, it was difficult for us to bathe or maintain cleanliness, resulting in us going for days without being able to wash ourselves or change into new clothes. The fighting started to loom nearer to where we were staying, by which point we hardly had anything to eat. Around this time, our grandfather died; having buried him, we kept moving from place to place. Eating only that which we had, we were caught in the middle of the fighting, unable to escape the area or return to our home. After constant displacements, we finally reached Mullivaikkal.

In Mullivaikkal, we stayed in a tent at the start. The texture of the ground was not suitable for digging a bunker. As it was full of thorny bushes, it was even difficult to walk on. Given that it would be nearly impossible for us to dig a bunker, we decided to hire casual labourers to dig it for us, who, instead of demanding pay, only asked for food as remuneration.

Usually, we would boil rice, drink the water as porridge in the morning and then eat the leftover rice with fried or charred chillies in the afternoon. It was what we also gave to the labourers as food. Around this time, distribution of ‘Mullivaikkal porridge’ began. We could only eat it if someone, usually men, went out and brought a portion for us. I was instructed to stay inside the bunker as our surroundings were constantly being bombed, which also prevented us from going out to collect drinking water. One of our relatives, who used to go to the sea to catch prawns, got hit by a shell on his way there and died.

Inside my bunker, I had put up iconographies of Jesus Christ and the Virgin Mary. I would pray the rosary. Every time I finished praying the rosary, the sound of the explosions outside would stop. I would believe that it was due to my prayers that the explosions stopped, even though that was realistically not the case. One day, a ‘five-inch’ shell fell inside the bunker behind ours, killing a person inside. On the same day, owing to the sweltering weather, many in the bunkers were afflicted with diarrhea. To relieve themselves, they had to go to the Nanthikaddal constantly. With shells falling all around us, it was nerve-wracking to run past the shelling. The attacks were usually worse in the evening.

On 16th May, having dressed my sister’s baby, I was waiting for a moment to go outside the bunker. Given the scorching climate, one could hardly stay inside the bunker for long. However, with no safe alternatives, I ended up staying inside the bunker, playing with my sister’s baby. Around 4.30p.m. or 5 p.m., my sister stood at the bunker’s entrance. Upon seeing the mother, the baby started to crawl towards her. The baby was just in underwear, so I tried to get hold of the baby’s legs to prevent from crawling away.

The baby kept struggling to go to the mother, and I was pulling the baby back by the underwear; at one point, the baby’s underwear came off as I pulled, leaving the baby free to crawl outside the bunker towards the mother. As I remained inside the bunker, all I heard was silence. A few moments later, I heard my mother scream. When I looked outside, she had the baby in her hands. She was shaking the baby, but the baby did not move. A piece of shrapnel went through one side of the baby’s head and came through the other side. I can still remember the way my mother looked vividly, with blood streaming down her own face from pieces of shrapnel, almost like the face of Jesus on the Cross.

I suddenly went into a trance, unable to fathom anything. I could not even cry due to the shock. When I came out of the bunker, I saw several injured relatives and quite a few dead bodies. Then my attention turned toward my sister. She had a severe injury on her head; and her entire back was gored and disfigured from all the shrapnel, with the blouse she was wearing torn to pieces. She was unconscious and did not know that her child was dead. She was taken to the nearby makeshift hospital, where a nurse (volunteer civilian) cut her hair, cleaned her wounds, and tried to stop the bleeding with sanitary pads. Her shoulder and back were filled with wound pits from the shrapnel.

That same night, most of those that stayed with us started to move out. As the baby’s body started to discolour, we clothed the baby in a christening gown as it was blessed, dug a hole, wrapped the baby in more clothes to prevent the mud from seeping into the body, and buried the baby. In anguish, wondering what good God was for, I broke the iconographies of Jesus and the Virgin Mary and buried them with the baby. After that, we left that place, holding each other for support.

We laid my sister on the only bicycle we had and pushed it down the road. Many that were on the cusp of death told us to leave them behind in order to save ourselves.Unable to provide any help, we went past them without doing anything. When we reached the main road, we saw fire on both sides. I still see that scene in my mind- like those that are depicted in Hollywood movies – of vehicles being engulfed in flames on both sides of the road. Having drank nothing for a whole day, I gulped down, with no forethought, a bucket of water that I stumbled upon on the road. While I was quenching my thirst, a pungent smell started to waft out of the bucket and within seconds I realised that the water had been used to rinse the wounds.

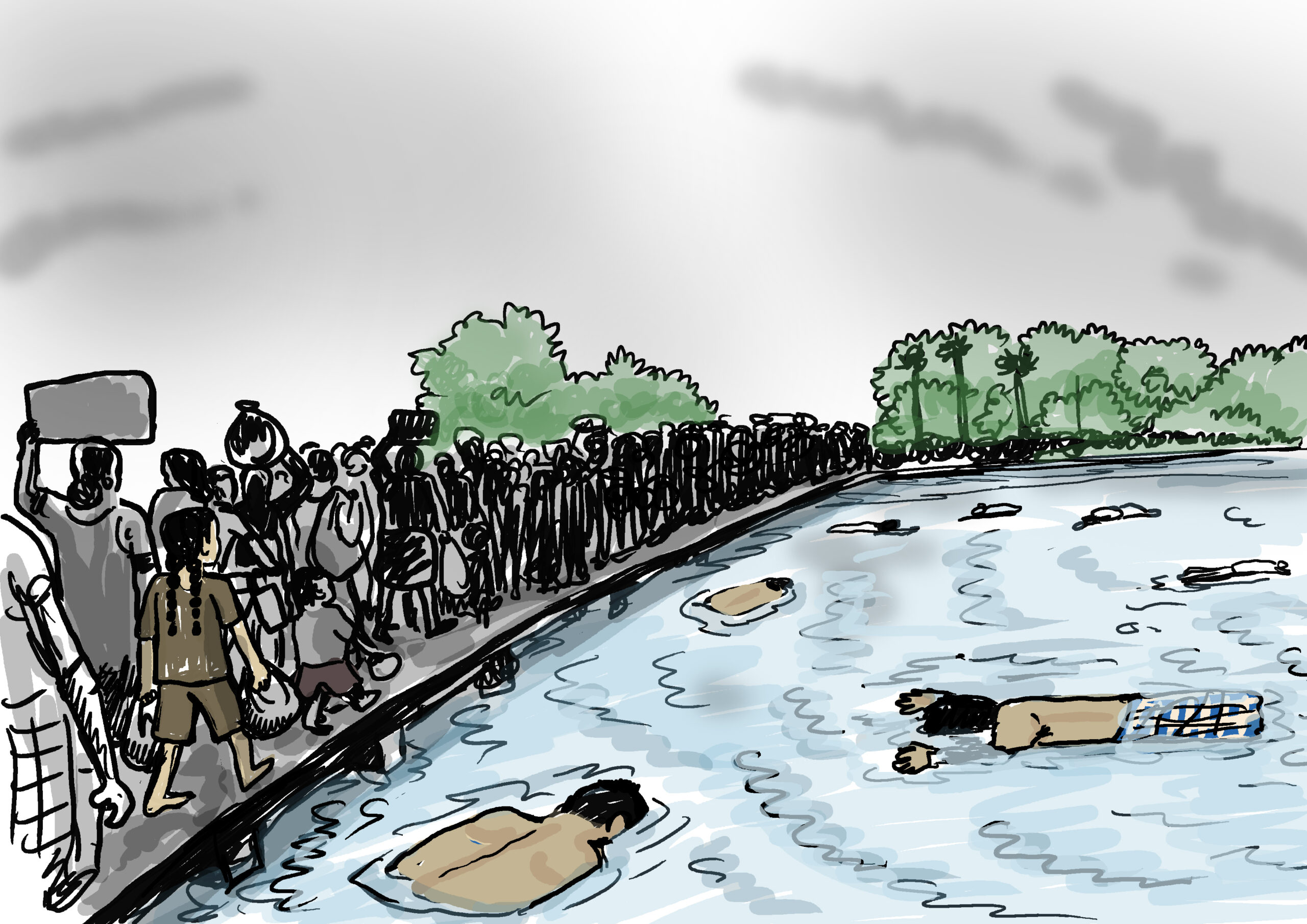

We did not know at that time where we were or into whose territory we were moving. When we were near Vattuvaakal, we saw numerous dead bodies lying around as if they were pennies that someone had strewn on the ground. We deduced that they must have been lying there for some time because dust had settled on the bodies, and nobody was there to bury them. In the Vattuvaakal Sea too, we saw bodies floating; they looked pale and fermented, similar to fermented fish.

The injured were being hauled inside vehicles. My mother, though she had no severe injury, decided that she could not let my sister go alone and hence got inside the vehicle. Back then, I did not know the location of where they were being taken. My brother, my father and I, along with some of our relatives, were hauled in another vehicle, where we traveled for almost a whole day without any food. We drank the remainder of the gripe water that we had kept for my sister’s baby. Most of us drank water when the vehicle stopped for a while, even though it was filthy, almost the colour of tea.

We then had to get past a military checkpoint. Everyone who wanted to get past into the territory controlled by the Sri Lankan army had to undergo a strip-search. My brother and father went through one tent, and I went through another. At that time, I was wearing brown trousers and a brown blouse.

I tried to convince my father and brother that going through security with no clothes on was not a big deal. Nevertheless, if I had had my mother and sister with me when I went through it, it would have provided some comfort. Having to go through such a humiliating experience alone was harrowing. As I was only 16 at the time and not fully an adult, I did not think much of it. I feel anguish whenever I think about it now and the fact that it was something all of us had to endure.

Having traveled on a bus for a whole day, we were finally taken to Zone 4. One month later, we managed to communicate with my mother and sister, and we learnt that they had spent those days – the days they were separated from us – in a hospital in Padaviya. Mother told us that going with my sister was a good call as she could help her. While in the hospital, my sister tried to run away several times in pain and sometimes would howl at nights thinking about her baby; my mother fortunately was there to look after her.

Unfortunately, many who escaped the war, died in the camp due to an outbreak of illness. My cousin was amongst them. I myself was seriously ill and was on the edge of death before miraculously recovering. Many of the illnesses that afflicted us were the result of the unhygienic food and water that we had consumed during the war. Although my sister was initially told that she would never be able to conceive again owing to injuries in her waist, she fortunately gave birth and now lives happily with her new baby. My mother occasionally experiences sharp pain caused by shell shrapnel still lodged in her mouth, particularly inside a tooth. I still find solace in the fact that they are still alive. My father too, despite still suffering injury from a claymore mine, is still alive. Everyone surrounding us in one way, or another has been negatively affected by the war and the shell attacks. My sister has just turned 39; the injury that she sustained in her head has gradually caused her to lose her eyesight. My brother has shrapnel still embedded in his body, the removal of which could cause him to become catatonic and paralysed. He cannot do hard labour, nor can he stand in heat for too long.

It is by the grace of God that I have no physical injury. However, I am devastated psychologically. I could not outwardly express my anguish and pain when the war was being waged and nor could I have afforded a mental breakdown back then. All my feelings were frozen. Although my faith in God had diminished after the death of my sister’s baby, I doubt we would have been able to endure all this and come this far without God’s grace.

I visited the places that we had stayed and made tents during the final phase of the war. I discovered the pieces of the iconographies of Jesus and the Virgin Mary that I had destroyed but could neither find the baby’s bones nor the baby’s clothes. We had buried countless people there and had abandoned many people who were nearing death. I could not find a single trace of them, not even a bone.

We are distraught by the harrowing experiences that we have been through. Although we act as if we have not been affected by these experiences, it is far from the truth. No one can easily emancipate themselves from these experiences. The trauma and the post-traumatic stress disorder accompanying them will be with us for a long time. Even now when I hear a loud sound, I run away and hide.

We know why and how the war was waged and how it was brought to an end. We regret that the subsequent generations have not fully grasped this information. Though the war has ended, we are prevented from living our lives in peace. We are still under military control, and the ex-cadres are under constant and heavy surveillance. The oppression against us still continues. The younger generations have started to understand that it was the oppression that led to the war. We might have found solace had we at least been left alone to peacefully rebuild our lives after the war.

I work for a non-government organisation. Beyond that, I also engage in social activism on a voluntary basis. Most of the work I do concerns women’s rights, immigration and emigration and livelihoods. It is the work concerning livelihoods that engages me the most. There are countless people in need of assistance. Although much assistance is available, it is not generally distributed on a well-researched need basis. It gives me satisfaction to identify people in dire need of assistance and make arrangements so that they can receive them. I have endured so many harrowing experiences, and now, fulfilling the needs of the war-affected people gives me immense satisfaction.